YOUSSEF NABIL - ICONOGRAPHY OF A REAL AND IMAGINARY EGYPT

ICONOGRAPHY OF A REAL AND IMAGINARY EGYPT

Youssef Nabil left Egypt in 2003. yet somehow He never left. With his hand-painted photographs and videos he created his own personal iconography of the Egypt he loved, the Egypt that once was and he wishes to preserve. Inspired by cinema, it is an imaginary Egypt, yet perhaps real nonetheless.

Nabil, you seem to move around quite a bit. Where are you at the moment?

I am currently in Brussels for my exhibition opening at Galerie Nathalie Obadia.

Normally you live between New York, Paris and London?

Not London. I go there quite a lot, but I currently live between New York, Paris and Miami. At first I was thinking of moving completely from NY to LA, as I was missing the sun I was used to while living in Egypt, but I realized I would be too far removed from my life in Egypt and Europe, so I opted for Miami. I love it. It is only two hours from New York and so whenever I need some sun or just want to escape the craziness of New York, I fly to Miami.

Do you still visit Egypt? And if you were in Egypt right now, where would you like to be?

I normally go twice a year, but in 2017 I went five times. There are many parts of Egypt I like. I love Cairo, but these days I notice I am having more difficulties with crazy cities like Cairo or New York. So, right now I would probably want to be in upper Egypt, near the Nile around Luxor, for example, or in Alexandria on the Mediterranean.

Why did you leave Egypt in the first place?

I felt I had to leave because photography as an art form was not very appreciated in Egypt. By that time, I had exhibited in some of the best galleries, but I felt that to continue to grow, I had to leave.

You should know that when I started in 1992 fine art photography was nonexistent in Egypt. You had the old photography studios in downtown Cairo, with photographers like Van Leo and Arman, but they mainly did portraiture. And the galleries at that time did not exhibit photography.

I managed to change that. But by 2003 I felt I could not grow any further. In addition, I did not have any relations with the Ministry of Culture, which perhaps could have opened doors. Also, being able to technically print my work was an issue, as it became harder to find the right paper. And I always had censorship issues, as my work deals a lot with the body.

Long story short: I just felt I had to leave one day. And that one day came in 2003 when, following a show in Alexandria, the French Minister of Culture approached me. He loved my work and offered me a one-year residency in Paris. I liked Paris and stayed two more years before moving to New York in 2006. And ever since I have kept the habit of moving back and forth. I have my studio in New York, but I print in Paris.

Would “self-imposed exile” be a good description of your current state?

Exile contains an element of force. It means the door is closed, you cannot go back. That is not the case for me. I regularly visit Egypt. For me leaving Egypt was a choice. I simply felt I had to leave to be able to create freely and have a future as an artist.

It is said that it is harder to live through a crisis when you are not there. How did you you experience the dramatic events in Egypt in 2011?

That is very true. I was in New York when the 2011 revolution started and I was checking websites and switching from channel to channel all the time. I was worried sick about my family, calling them all the time. In fact, it got so bad that I got at one point physically sick.

No need to go into details, but it is definitely very difficult to be away from the country and people you love in times of crisis.

“I started doing my own thing, creating scenes, inspired by cinema, and making images. It was the closest I could get to doing cinema.”

Did it influence your work?

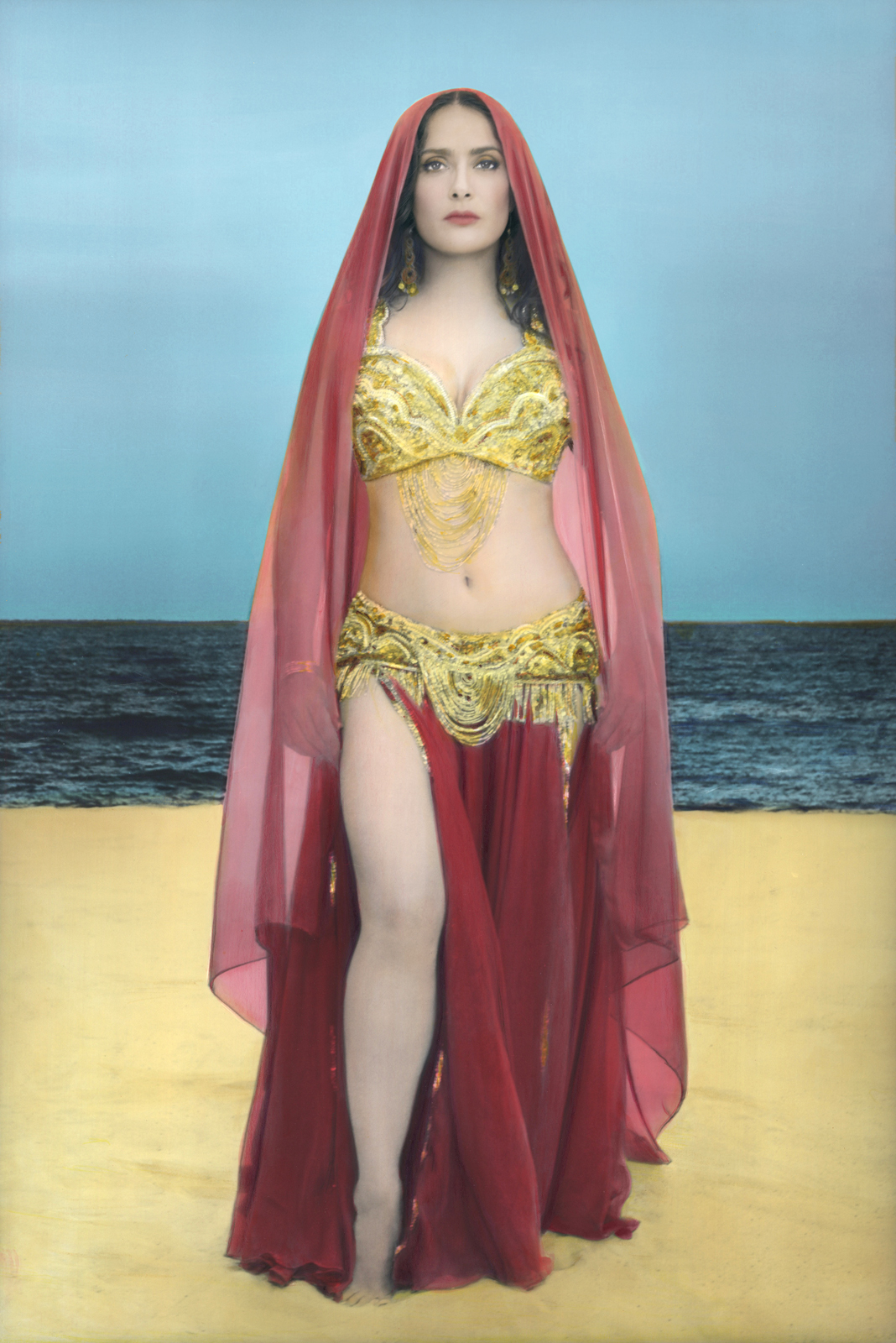

Yes, it did. The events of 2011 and especially the Muslim Brotherhood coming to power shortly after, led me to do my project I Saved My Belly Dancer. One of the first things the Muslim Brotherhood did when they came to power was to close down 12 night clubs. Prior to that there had already been issues like banning bikinis on the beach. It was one thing after another in a very short period of time.

That reminded me of what friends had told me about the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran. The Islamic regime had started by banning unveiled women from government buildings, then they banned them on TV and finally also on the street. I felt that by banning belly dancing, Egypt started to introduce the notion that a woman is not free to express herself. When I was young, belly dancing was something we used to see all the time. I think it is a great art form. And for me it has always also been a sign of how free we can be as a society.

What's the status of belly dancing today?

Belly dancing is of course not an issue on its own. There are many issues related to a woman not being as free as a man, not just in Egypt but in most of the Arab world. And if a woman uses her body in a sensual way, the closest image that comes to mind is that of a prostitute. And, I must say, that also exists. There is a lot of bad belly dancing. But the art that I grew up watching used to be highly respected. It is very old. They found images of belly dancing from pharaonic times, of course it was not exactly danced as they did in modern times, but for me belly dancing has always been an integral part of the Egyptian identity.

In I Saved My Belly Dancer you worked with Salma Hayek. How did you meet her? And how was it to work with her?

I first met Salma at an art event in Paris. I knew she has some of my works. She had done the movie on Frida Kahlo and has the work I did about Frida “My Frida", 1996 in her art collection. So, I introduced myself and asked her if she would be interested to be part of my new video, I Saved My Belly Dancer.

‘But I don’t know how to belly dance,’ she said. ‘But you’re half Lebanese,’ I said. “We’ll find a solution.’ So, she invited me to LA. I stayed a week at her house to get to know each other, watch belly dancing films, and help her to get into the character. To me, Salma was always an Arab. She is Mexican, of course, but she has the face and the body, the name even, of an Arab. But this was the first time ever she played an Arab role. I first tried to shoot in Morocco, but there they did not know how to make belly dancing costumes. Then I went to Egypt, but there I ran into censorship issues. So eventually we decided to film in London using a green screen, while I shot the background in the Grand Canyon. It was a huge project in terms of everything. It took about three years to make. But Salma was always very nice, very professional and very inspired. She is an artist in her blood.

Prior to working with Salma Hayek you have worked with many Arab and Western celebrities. Does it make a difference to work with one or the other?

No, not really. To me it does not make a difference if someone is French or Egyptian or a celebrity or not. I also photograph my friends, or friends of friends, and once they are in front of the camera I forget who they are. There is no special treatment for anyone.

It takes a lot of patience to work with some of the people I photographed, like in the case of Catherine Deneuve, Robert De Niro, Louise Bourgeois or Zaha Hadid. It can take years to get someone in front of the camera, because I work on a personal level, never through an agent. So, I wait for a chance to approach someone, mostly through people I know. The preparation can take years, but while I am in studio shooting, I only think about their outfit, make-up, hair, background, light, etc. Then when the shoot itself starts, I'm not there. I am somewhere else. It is only when I develop the films and see the contact sheets that I realize I had Catherine Deneuve in front of me.

I have visited Cairo numerous times and always loved it. It is such a city of color and wonder. What was it like to grow up there?

Well, I must say I was not your typical Egyptian boy. First of all, I attended a French school. So, I grew up with French books, watched French movies and listened to French songs. To me, this was a world of freedom and beauty, which sharply contrasted with everyday life on the street, where you always had to be careful. Secondly, I grew with two religions. My mum was Muslim, my father Christian. He converted to marry my mum. To us, religion was never an issue. We regarded them as different, yet essentially the same. In real life, however, I would be confronted with people badmouthing the one or the other. So, I grew up between these very conflicting worlds.

On top of that, I was quite introverted. Very timid. Talking was a big effort for me. Not that I was anti-social, but I really needed to know someone before I could open up. I think I have always been more of an observer. I was always watching people and even started to see my own life through the eyes of an observer.

And then there was Egyptian cinema of course …

Yes, Egyptian cinema was a very important part of my childhood and is a big influence on my work. As a child my life was all about going to school, coming back home and watching movies. I would do my homework with one movie, have dinner with another one and fall asleep with a third.

And I was always asking my mum who is this actor or that actress, and where are they now. And often the answer would be that they are all dead. I was shocked as a child. I realized I was watching and loving and admiring all these beautiful dead people. So, at a very young age I became aware that we are all going to die. And I think this is what made me want to preserve the things I love. To create this big family. Most of my friends are in my work. I do a lot of self-portraits. And I portray the actors from the movies I love.

When did you first realize you wanted to become an artist?

There never really was a specific moment as such. I knew from a very early age that I wanted to work with something visual. I loved cinema and storytelling. Following high school, I applied to the main art academies, but I was rejected every time. I was a bit depressed for a while, but then I started doing my own thing. Creating scenes, inspired by cinema, and making images. It was the closest I could get to doing cinema.

At first, I worked only in black and white, because I refused to work with color film, so I decided to learn how to paint manually the photographs myself in order to keep that old feel. Little by little I became known, got a few assignments, traveled abroad and eventually did my first exhibition. That was all very exciting, but not something I ever imagined as a child.

How does a young and aspiring artist from Cairo become an assistant to both David LaChapelle and Mario Testino?

That is a funny story actually, which proves my belief in destiny. As I said, I had been refused by just about every art academy and every art gallery I could find, and so I started to do my own photography. Soon after, one day in 1992, I was doing a shoot with a friend in the garden of a hotel in Zamalek (Cairo). David LaChapelle happened to stay in the same hotel and approached me. He asked what I was doing and went on to explain that he was facing all these problems doing a shoot for Condé Nast Traveler. The production house was asking him for too much money and he asked if I could help.

Now, I did not know him at the time, but I knew the magazine. So, I agreed, but told him I did not want any money for it. I just wanted to help for the experience. A few weeks later he called me from New York, saying how touched he was by me helping him and that he really liked my work. He also knew I could do with some help, so he invited me to come to New York and work as his assistant, which I did in 1993 and 1994. Some years later, Mario Testino came to Cairo and he was looking for an assistant. I applied and he chose me. After the job in Cairo was done, I continued working with him for two years in Paris. To me, these encounters always felt like they were meant to be. I could not take the classic path to become an artist or filmmaker, so I was offered an alternative route.

You are famous for your “hand-color gelatin silver prints” Now I am sure that is a whole lot easier said than done. Could you tell us a bit more about the process?

Gelatin silver print is just the technical term describing the most common process for making black and white photographs since the 1890s. The hand-coloring technique I practice is one of the oldest techniques of hand painting photographs. I learnt from the last re-touchers operating in Egypt. In the old days the portrait studios would still offer you a black and white or colorized portrait. By the early 90s there were a few of these re-touchers left. Maybe 10 or so.

They were old and out of a job, often living in very difficult conditions, some I found living in a basement. So, that’s how I tried to find them in Cairo and Alexandria, offered them money in order to learn from them that old photography technique I was in love with. I use water color, pencil, charcoal and sometimes oil paint. The main difficulty is how to deal with the photography paper. You cannot use too much water.

Your work has been shown and collected by some of the most prestigious galleries and museums in the world. How is your work perceived in Egypt?

The young generation has a great response and a few people collect my work. Not many. Maybe five. But I am Egyptian, I am from Egypt, my main inspiration is from there, so of course I would love to have a major exhibition in my own country one day. At the moment, however, I think the sensuality of my work poses a problem for the censors.

Do you have hope for Egypt?

I have great hope in the young generation. They are so connected these days and so aware. Things will have to get better.

INTERVIEWED BY PETER SPEETJENS